By Alison Preuss

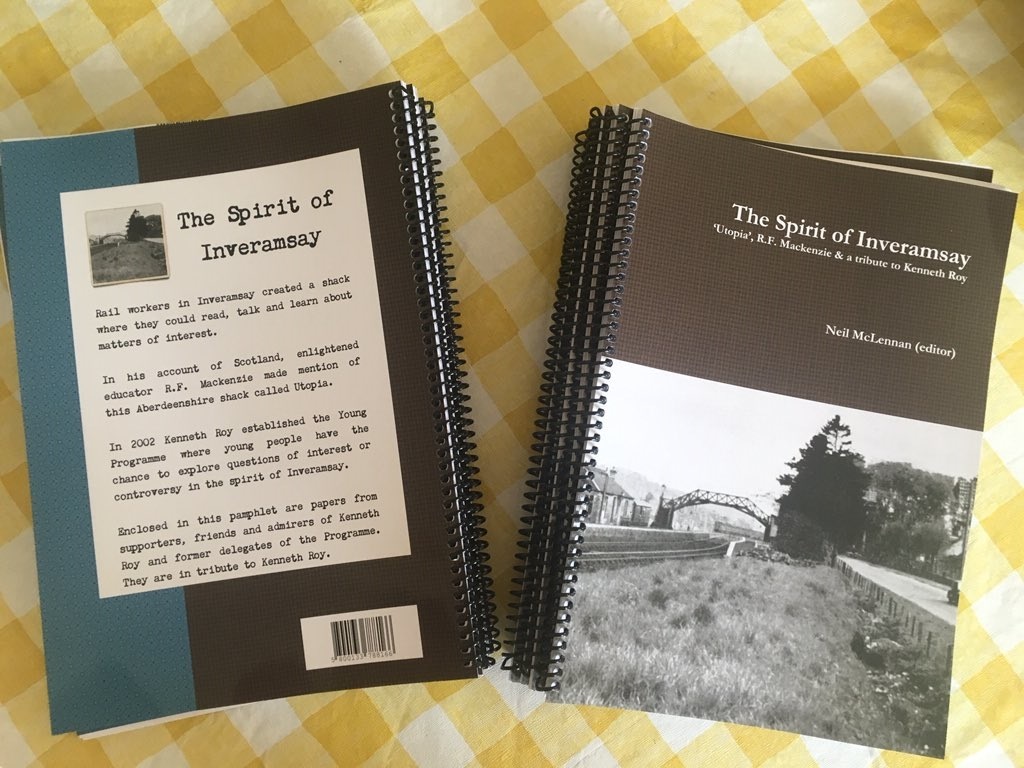

Published in The Spirit of Inveramsay: ‘Utopia’, R.F. Mackenzie & a tribute to Kenneth Roy (edited by Neil McLellan)

Parallel Lines: a tribute to Kenneth Roy

In October 2010, an email from a senior Scottish politician landed in my inbox asking ‘Did you put Kenneth Roy up to this?’ The ‘this’ was a three-part Scottish Review investigation which had just debunked the government’s flagship GIRFEC (‘Getting It Right For Every Child’) policy as a surveillance scheme in woolly wellbeing clothing.

Read the series: Big Brother Scotland / In the nightmarish world of mass snooping on children, Scotland leads the way / In Scotland’s new world of electronic child surveillance, debased language conceals what is going on

Until Kenneth decided it mattered, nobody had paid much attention to those of us who had long been challenging the fake narrative around the policy. A few days later, the senior politician emailed again with a promise of robust privacy safeguards. Of course they never materialised and we had to wait six years for the Supreme Court to settle the issue.

Fast forward to 2019 and we are still awaiting action to undo the damage caused to families by premature implementation of a policy that permitted the collection and sharing of their personal information without consent or other lawful necessity.

Following Kenneth Roy’s memorial service, held in Glasgow on 14 March 2019, I was prompted to revisit these old emails by an invitation to contribute to this commemorative publication, which also caused me to reflect on our parallel lines of enquiry over the years, long before we became acquainted.

Image credit: Scottish Review

Back in 2001, as Kenneth was writing about Inveramsay, I was co-founding a children’s rights group in a parallel Utopia which doubled as my friend’s kitchen in east London. There, like the autodidacts of 1920s Aberdeenshire, we would ‘sit into the night discussing everything in heaven and earth’.

We resolved to ‘do something’ about the growing threat to children’s rights from the proliferation of government databases, all of which hung on the shoogly premise of preventing state-defined ‘social exclusion’. I was handed the Scotland brief and press officer’s job.

Thanks to that healthy spirit of enquiry, we were soon on a roll with no shortage of injustices to challenge. Teachers told us they were being rail-roaded into collecting vast amounts of personal data on children and families without proper justification (e.g. child protection concerns), yet when we highlighted the human rights implications, we were dismissed as ‘hysterical home educating housewives’.

Our concerns were soon validated when England’s DfES won Privacy International’s ‘Most Heinous Government Organisation’ award for the pupil tracking system we had flagged. Meanwhile in Scotland, we had seen off an attack by the then Executive on home educators’ Article 8 rights, having galvanised support from opposition politicians .

Many years of campaigning later, our bête noire, the controversial ContactPoint database, which held details of every child in England (except those of celebrities, MPs and others whose privacy was too important to compromise), was finally abolished by the UK’s incoming coalition government.

Sadly, the contagion had already spread and Scotland was becoming thirled to the same surveillance agenda. A change of executive in 2007 did little to contain the datafication disease which soon had a catchy new name, GIRFEC, and a supporting cast of acronyms, slogans and risk indicators against which every child’s progress towards government-defined outcomes was to be mapped.

In 2009, I had raised my concerns directly with my MSP, John Swinney, who assured me that adequate safeguards were built into the GIRFEC model, although our evidence to the contrary had already formed the basis of a briefing paper we had shared with ministers and others. FOI requests and minutes would eventually confirm a ‘conscious decision’ to conceal how personal information was to be collected and shared without consent in order to avoid any ‘adverse reaction’.

Despite Scottish Review’s revelations and evidence from grass-roots groups who knew the policy was legally and practically problematic, the government carried on regardless, co-opting all the children’s charities along the way. They ignored dire warnings from human rights experts, including ours, who cited the same case law and ‘totalitarian’ references that would eventually appear in the Supreme Court judgment and are frequently highlighted by its president, Lady Hale.

The Children and Young People Act was steamrollered through parliament in 2014, as predicted. Although its information-sharing provisions were not due to commence until 2016, the information commissioner had unfathomably issued revised ‘advice’ in 2013 that endorsed a lower, woollier threshold of ‘wellbeing’ to encourage the sharing of data without consent. That single catastrophic error of judgement opened the floodgates whereby personal information was not only being gathered and shared unlawfully, but victims’ legitimate complaints were also being wrongly dismissed. Despite its forced withdrawal in 2016, the 2013 ‘advice’, along with its erroneous wellbeing threshold, is still referenced in current public sector guidance. That really does matter.

It was only after a legal challenge by a coalition of charities and concerned individuals that the emergency brakes were finally applied to the runaway GIRFEC train. An attempt to pass remedial legislation has since been shunted into the sidings, while a parliamentary petition is calling for a public inquiry into the human rights impact of unlawful data sharing, past and present.

Nearly two decades on from the DfES’s ‘home educating housewives’ jibe, an academic tweeter recalled being told by an MSP that it was ‘just some homeschoolers’ who had opposed the legislation (subtext: we didn’t matter). Only after reflection on the humiliation of a court defeat was it conceded it had been a mistake to shoot the messengers without bothering to engage with their message.

People did highlight anxieties about the provision for information sharing before the original Act was passed. But because they were the “wrong people”, they were ignored.

Like the Inveramsay railway clerk, Kenneth Roy considered no quarry too big to swoop upon and left no questions unasked (or answers unquestioned) in order to satisfy that innate spirit of enquiry. Although I was just one among many passengers who had the good fortune to alight on the platform of his Utopia, Kenneth still made me feel that I mattered. I very much doubt that senior politician will even remember our email exchange, let alone the broken promises.